Moondust

Countdown has started. It’s official; it’s a go.150 sols, and that will be all.

I sit down at the control deck of my spacecraft in Lower Mars Orbit and fire the virtuality on. Sakaji’s golden, glowing silhouette pops up in front of my eyes, soothing and alluring at the same time.

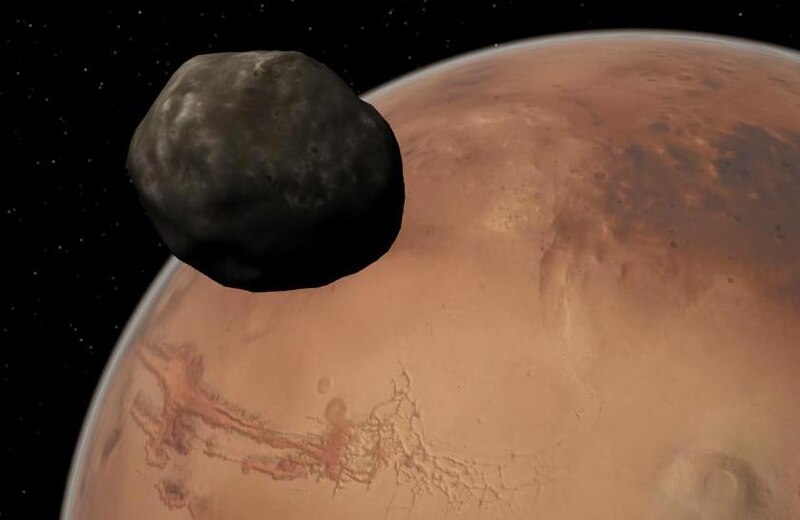

“Phobos is doomed, Sakaji.”

“Phobos was doomed since the beginning, Captain Keller,” she says, a kind smile on her holographic face while she begins computing the latest data I’ve logged on the system. “Its Roche limit would have eventually been reached.”

“Yes, in ten million years. I could’ve lived with that.”

Now, no more Phobos in five months. Its small, misshapen body will be blasted and shattered in tiny brownish particles, left fluttering around the Red Planet.

“Are you ready?” Sakaji sounds concerned.

“Never going to be ready. I’ll just obey.”

“Think positive, Captain.”

“That’s positive,” I reply, looking at the simulation results pouring out of the processing unit and bundling up nicely on the screen hyperplans. They look like equations in a now-forgotten numeric system. “Haven’t defected, have I?”

Not yet, no.

—

130 sols to go. 130 sols, and they keep talking.

Cydonia proposed it first, Mons Olympus came along. In principle.

They still disagree, the two Martian main settlements, about the way it has to be done, timescale, modalities, staffing. Some surprise; they disagree about everything, except for the very decision to go for it. Nobody on Mars doubted for a single goddamn moment Phobos had to die and be buried in form of particles. Advice poured in from Earth, too, loud and smug as usual. Dangerous endeavour, you Martian boys, don’t be too cocky.

Not a single one asked for our opinion –us, the 1,500 lost souls of the Stickney Settlement, us who used to call that rock home. Derelict and unappealing and crater-ridden, certainly, but home is where your heart is, right?

Not any longer.

—

110 sols, and I hadn’t got used to the idea yet. My nights are full of nightmare, in those rare instances I manage to sleep at all. Most of the times, I just lie down and look up at the glass ceiling, staring motionless at the darkness that will soon claim my colony.

“Stickney as an artificial gravity study facility was no longer needed,” Sakaji argues. “On the other hand, having Phobos as a set of planetary rings will be precious.”

“To whom?”

“Mons Olympus, for their pilot training. Cydonia, for its areostationary satellites. And if you think about outer-system missions-”

I don’t listen to Sakaji any longer. To me, it’s out of envy of the Saturn colonies and their breath-taking, sparkling rings. The symbol of majesty in the Solar System. Odd to be so governed by passions. You’d imagine vanity has no place out here. Yet, the rationality humankind had to develop to survive in space doesn’t extend to an inch more than what is strictly necessary.

“No. It’ll only be beautiful.”

—

95 sols and we’re now down to operations, checking mission’s details, selecting the Destroyer team and its weapons.

Not enough power, and nothing will happen; too much, and you’ll flood the Martian surface with a meteorite rain that would make the end of Cretaceous landscape pale in comparison. It might well backfire, this plan, and goodbye Cydonia.

I may overshoot, too.

—

35 sols, and it is training time for the R-Day. We fly out there every morning, my squad and I, pushing limits, testing weapons. You can’t hit from a distance: you’ll need to get near, being surgical, accurate, using the right amount of energy and not a joule more. With the risk of being smashed by swirling moon particles. Safety will be in escape speed and appropriate trajectories. And lots, lots of luck.

We know, and we train at night, too, to binge drinking and unbridled debauchery.

I’m the one condemning my people to oblivion and my home settlement to become moondust and a soon-forgotten history. I guess I’m entitled to psycho-drugs, underground rave parties, ear-splitting rock music, and a few hours of oblivion myself.

—

“Roche Day’s upon us, Sakaji.”

I suit up, position the visor on my face and check out with my Destroyer unit. If someone screws up today, I’ll be part of that moondust myself.

“Yes.” She voices my thoughts in her exotic accent. “It may end badly.”

“Doesn’t bother me, so it shouldn’t bother you. They’ll incorporate you again the day after, in the same shade of gold. Me, I’ll be gone for good.”

“That’s the point: I don’t want to. I love you, Captain.”

“The Cydonians have programmed you well for my last mission. Is this part of the hero farewell package?”

“You're the best. It won’t be your last.”

“As a Phobos national? Yes, it will.”

—

Take off.

You take off.

Shoot.

You shoot.

Come back.

You come back, if you can. Listen to the music, sport: some of us did not.

—

I stand by the window of my glittering new house -can’t call it home, can I?- in the posh Cydonia. Perks of being a space hero, I suppose. You got to be one for a residence permit in the most elitist Martian colony.

The mission was a complete, record-breaking success; nobody had ever accomplished what we did out there. Only minor damages across all the Martian settlements and limited casualties. And now, day after day, we stare at them, the Moondust Rings, forming in front of our telescopes, one piece at a time.

Sakaji’s no longer with me. She trains space operators in Mons Olympus now. I can’t complain; she’s the most experienced AI around, the only one that has proved her value in the field, so to speak. I understand, but I still miss her presence on my deck.

Not that I am going to be alone for much longer. With a gesture in between concerned and awed, I touch my belly. My daughter is moving. She’ll be born the day we have the best view of the new rings, I’ve been told. I have no idea who her father is –one of the pilots of my unit is my best guess– but I’m not her mother either. She is made of the same matter of planets and stars, of the dust of our vanished home and the tears of its exiled people. Space will be her oyster.

I look up, at the transparent ceiling, and I can almost see the rings in their full splendour. They are thin, ghostly particles, dancing around in a hide-and-seek game every Martian is playing now, with mixed feelings but undivided attention. You can sense them hovering and lurking in the dark even when their view eludes you. You can listen to them too, like I do every night.

My hand reaches out for the plasma radio and switches it on, loudspeakers at full volume. I close my eyes, breathing, letting it go, while the music of their waves sings my moondust baby lullabies.